China's Big AI Diffusion Plan is Here. Will it Work?

A bearish and bullish case for the major "AI+" initiative

Hey there,

Welcome to my first Substack post. A quick introduction to me: I’m a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where my research focuses primarily on Chinese AI governance, specifically how the AI policymaking process works over there. (An overview and a deeper dive on that). Before that I was a journalist in China and wrote a book about California-China ties.

I’m not sure exactly how I’ll use this Substack — probably a bit of experimentation in terms of form and content — but I’ll primarily be covering China, AI, and related odds and ends.

[Note after I’ve finished writing this piece: I initially intended this to be a pretty short sketch of an argument, but as I got going it grew into something much more in depth. It gets into big questions on the trajectory of Chinese AI development, so I think/hope it’s worth your time. But if you’re not looking for that kind of a longread every time I’d still encourage you to subscribe — subsequent pieces will take different formats and likely be more concise. Famous last words for a writer, I know…]

OK - let’s dig in.

On August 26th, China’s State Council released a much-anticipated policy document on how to implement the national “AI+” initiative. In terms of Chinese AI policy documents, this is quite a big deal. I’d rank it below the 2017 national AI plan and the 2023 generative AI regulation, but above a raft of other regulations and standards that have come out over the past ~8 years (my incomplete catalogue of those here). As with the 2017 AI plan, this is also likely to set off a chain reaction of sector-specific subsidiary “AI+” policy documents, such as last week’s “AI+Energy” policy.

Below I’ll explain:

Goals and structure of the AI+ policy

And what the hell does “AI+” mean?

The bearish case against AI+

Cash-strapped local governments, slumping private investment, difficulty of integration.

The bullish case for AI+

“Policy as permission”, (training) data unleashed, AI+Science

Conclusion

Where I land, tech booms as a driver vs. product of economic booms

Links to the text: I’ve had Claude do a machine translation and side-by-side comparison with the original Chinese. I haven’t checked the translation line by line, but what I did check looked good. You can find the original Chinese document here.

1. What is the AI+ plan and how does it work?

Overall framework:

The AI+ plan aims to turbocharge the diffusion and integration of AI applications throughout China’s economy, society and governance structures. In literal terms, the “AI+” refers to “AI+[a specific industry or sector]” — e.g. “AI+manufacturing” for integrating AI into Chinese factories, or “AI+healthcare” for integrating AI into the healthcare system. This “[Technology]+[Sector]” formulation originates from the “Internet+” plan of 2015, which I’ll describe more below.

The “big idea” articulated in the policy is that the deep integration of AI applications will re-structure China’s economy and society in fundamental ways, and this is the Chinese government’s roadmap for guiding and accelerating that integration. The really-quite-modest goals of the plan are using AI integration to:

“reshape the paradigm of human production and life, promote a revolutionary leap in productive forces and a profound transformation of relations of production, and accelerate the formation of a new type of intelligent economy and intelligent society.”

This all dovetails nicely with Xi Jinping’s big push for “new quality productive forces” (新质生产力) to become the driver of China’s next decade of growth. In a nutshell, “new quality productive forces” is shorthand for using technological innovation to upgrade Total Factor Productivity in China’s vast industrial economy.

Notably, the document doesn’t cite AGI as the driver of these changes, and it pays relatively little attention to frontier AI development in general. Instead, it’s focused on how the AI of today-ish can be leveraged to achieve the CCP’s economic, social and political goals. Analysts such as Julian Gewirtz have reasonably questioned whether this public focus on applications might be a smoke screen for the CCP’s actual focus on AGI. That can’t be ruled out and it’s possible a considerable amount of resources are being devoted to such a program (I’m sure our intelligence agencies are monitoring for it). But at this time, a plan like this will be the Party’s largest push to mobilize China’s scarce AI-related resources (money, chips, talent, bureaucratic energy) in the coming years, and directing that push towards applications is likely a sign that these remain the Party’s top priority.

As one Chinese security scholar working on AI issues phrased it on WeChat, “The next stage of generative AI isn’t AGI. It’s application scenarios!”

One final big picture note before digging into specifics. This is the highest-level document I’ve seen that directly addresses unemployment risks from AI:

“Strengthen employment risk assessments of AI applications, guide innovation resources toward areas with high employment potential, and reduce impacts on employment.”

This is just one sentence in a long document aimed at turbocharging AI deployment. But I think it’s a very significant one. Up until quite recently, unemployment concerns were not a major topic in Chinese policy discussion around AI — in informal polls of policy scholars it ranked quite low on a list of potential risks. But that seems to be changing. A spate of protests in Wuhan by taxi/Didi drivers over Baidu’s robotaxis drew national attention, and I’ve heard rumors that the NDRC (the economic planning agency in charge of AI+) is growing increasingly concerned about AI-induced unemployment, including commissioning a major study on the issue. This isn’t brand new — when I was in China in 2017, a researcher with the State Council’s main think tank told me about a study they were conducting on this. But both the technological and economic forces here have changed dramatically in the years since, and I’ll be watching this space closely going forward.

Ok, back to the policy document itself.

Targeted sectors:

The plan selects six priority areas for this integration:

AI+Science and Technology

AI+Industrial Development

AI+Consumption Upgrading

AI+People's Livelihood and Well-being

AI+Governance Capacity

AI+Global Cooperation

Each of those priority areas then has a number of more specific focus areas, some smart and some... questionable. For example, the S&T bucket includes a call to “accelerate the construction and application of scientific large models”… along with applying AI within philosophy research. The People’s Livelihood bucket includes calls to increase AI-assisted medical diagnoses… along with AI for “strengthening interpersonal connections, providing spiritual comfort and companionship” and more.

Aside from these priority sectors, the plan also includes several sections with (pretty vague) suggestions for improving China’s deployment of data resources, compute capacity, talent, etc. to support AI diffusion. These largely rehash existing government policies / goals, but I’ll flag some potentially new ideas and language below.

Milestones and metrics:

The policy sets ambitious goals for AI adoption in these areas, as well as broader societal impact:

2027: The penetration rate of AI devices, agents and applications will exceed 70%;1 “the role of AI in public governance will be significantly enhanced; and the AI open cooperation system will be continuously improved.”

2030: AI will “comprehensively empower high-quality development” and the penetration rate will exceed 90%, with the intelligent economy becoming an important “growth pole” for China’s economic development.

2035: China will “enter a new stage of developing an intelligent economy and intelligent society” that supports the CCP’s existing big-picture goal of “basically realizing socialist modernization” by that year.

Including specific metrics and timelines is nice, and these years + targets are guaranteed to be used by U.S. politicians pointing to the fact that China has a “plan” to use AI to dominate us in all of these sectors.

But when analyzing these high-level policy documents, the specific targets are often written vaguely enough to defy precise measurement. That’s because it’s not the targets themselves that matter for policy execution. It’s the signal they send, and the reaction they spark from actors across the CCP, state and wider economy.

How these plans typically work: “Call-and-Response” policies

The AI+ initiative follows in a tradition of Chinese tech stimulus policies that aim to accelerate the development and deployment of a new technology. Some examples of this include the 2015 “Internet+” campaign (the namesake for today’s AI+ policy) and the 2017 national AI plan.

These policy docs aren’t like pieces of legislation in the U.S. that prescribe exactly what will be done, by whom, under what authority, and with what level of appropriations. They are closer to Executive Orders, if EOs were vaguer and could galvanize action by all state and local officials, along with businesses, venture capitalists, university presidents… even Chinese parents deciding what their kid should study or what job they should take after college.

The documents often begin by announcing grandiose goals for the technology (“reshape the paradigm of human production and life”) and then rattle off hundreds of things that might contribute to that goal: specific applications, various types of incentives, and lots of nice things to “promote” and “encourage.” They make for strange and overwhelming reading if you take them too literally.

Essentially, these documents operate like a “call-and-response” between the top leadership and ministries + local officials / businesses around the country. The high-level policy document sends a clear signal to all Chinese officials (+private companies/investors and society writ large) that this technology is a priority for the top CCP leadership, and they will be rewarded for doing something, anything (see below) to advance it. If they do, officials can expect better performance marks and faster promotion. And historically, private companies and investors will rush into the sector, aiming to ride the wave of subsidies and preferential policies to windfall profits.

Here is a small sampling of these types of actions from a 2018 piece I wrote about how local officials were reacting to the 2017 National AI Plan. (The links are now broken, but all of these were all publicly announced projects at the time.)

Are you in charge of transportation for the new megacity of Xiong’an? Partner with Baidu’s self-driving project, Apollo, to demonstrate autonomous vehicles in the city. Head of the Changping branch of Beijing’s Public Security Bureau? Spend 2.75 million yuan ($437,000) procuring AI person-tracking software for security cameras. President of a mid-tier engineering university in Shandong? Open the province’s first AI research center focusing on medical and marine AI. Party chief of a Nanjing economic development zone? Pour 8 billion yuan ($1.3 billion) into an AI-focused venture capital fund and dole out 5 million yuan ($794,000) in R&D subsidies to each firm that sets up shop there.

This approach floods the zone of the targeted sector with a wide range of physical, financial, human and technical resources. Basically, it revs up the engine (or “primes the pump”) of the industry and associated research. Looked at individually, many of these actions are clearly wasteful — lots of technological “bridges to nowhere.” But if a technology is general-purpose enough, and if it’s economic upside is large enough, then in the aggregate these campaigns can pay off by turbocharging development and adoption.

Has it worked in the past? It’s impossible to fully disaggregate the impact of a policy from the existing industrial/technological momentum. And sometimes these policies are just a way for the gov officials to claim credit for what was happening anyway.

But for at least the 2015 Internet+ campaign and the 2017 National AI Plan, I watched them play out up close, and I talked with entrepreneurs, investors and students about them at the time. I believe they had a real material impact in turbocharging these fields. At the time, local governments around the country had the cash to throw at all kinds of projects, and the government had the ability to galvanize the private sector (and society writ large) to rush headlong into these industries in droves.

In the years following Internet+, we saw a tidal wave of new internet startups and applications that drove actual economic productivity and government efficiency. And in the wake of the national AI Plan of 2017 we saw a similar surge of startups, along with a major increase in the academic and research base of the industry.

2. The Bearish cases against AI+: Money, Trust and Integration Friction

In short, (1) China’s local governments don’t have the cash to run the typical playbook, (2) China’s VC / tech investment sector has been decimated and is less likely to rush into the new sector due to broken trust with government, and (3) deeply integrating AI into traditional sectors is simply far harder and more labor intensive than the relatively lightweight integrations of the “Internet+” era, such as mobile payments and online orders.

Historically, “Call and response” policies worked well when two conditions were met:

There was a ton of capital sloshing around the economy (both private and public coffers).2

Private investors and companies strongly followed the government’s lead because they believed there was lots of money to be made in the new industry-of-choice.

But this time around I don’t think those conditions hold.

I’ll start with government cash, and I’ll be relatively brief here. For local and provincial Chinese officials to carry out their “response” in the “call and response” policy cycle, they usually need to spend money (or forego the opportunity to collect it in taxes). There are some low- or no-cost policy actions that can be taken (and I’ll describe some for AI+ in the bullish case), but many of the actions in the typical playbook require significant financial outlays.

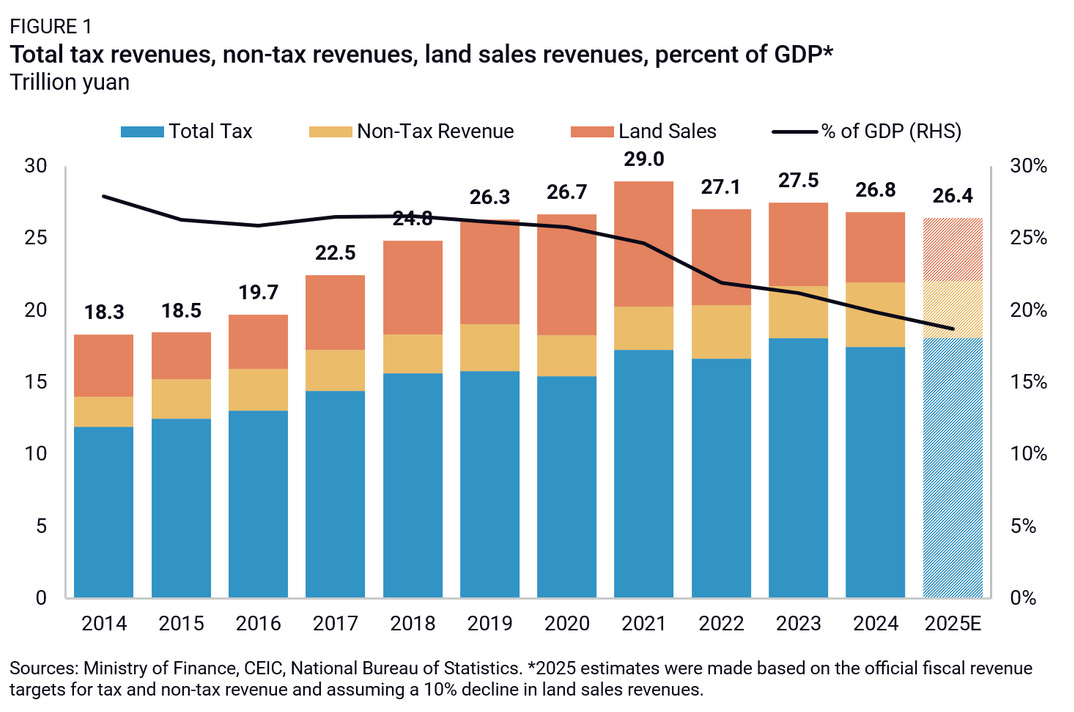

And Chinese local governments just don’t appear to have the surplus of cash on hand. That’s largely due to declining revenue from selling of public land (which basically printed money for local governments during the multi-decade housing boom), and largely stagnant tax revenues since 2021. See the below chart on declining fiscal revenues from the Rhodium Group, particularly the “% of GDP” line, which has gone from ~25% in 2015 to a projected ~19% this year.

This has effectively forced local governments around China to implement a variety of informal austerity measures (like not paying their employees and contractors) and illicit revenue generating schemes (like extorting businesses and rich people into paying new fines or alleged back taxes). These practices are not systematic across China, and we only get glimpses of what’s happening, but the picture that emerges is of local governments — and public institutions like hospitals and universities — who are really struggling to pay the bills.

For AI+ to really work you need these institutions to be ready to dole out cash on all kinds of related projects, but that doesn’t appear to be the case. Without the money to subsidize, procure, and pilot AI+ projects, you’re left with a lot of exhortations but no new incentives.

Ok, if local governments / public institutions can’t put down the money themselves, they can surely still galvanize (or force) the private sector into investing, right? I’ve got my doubts.

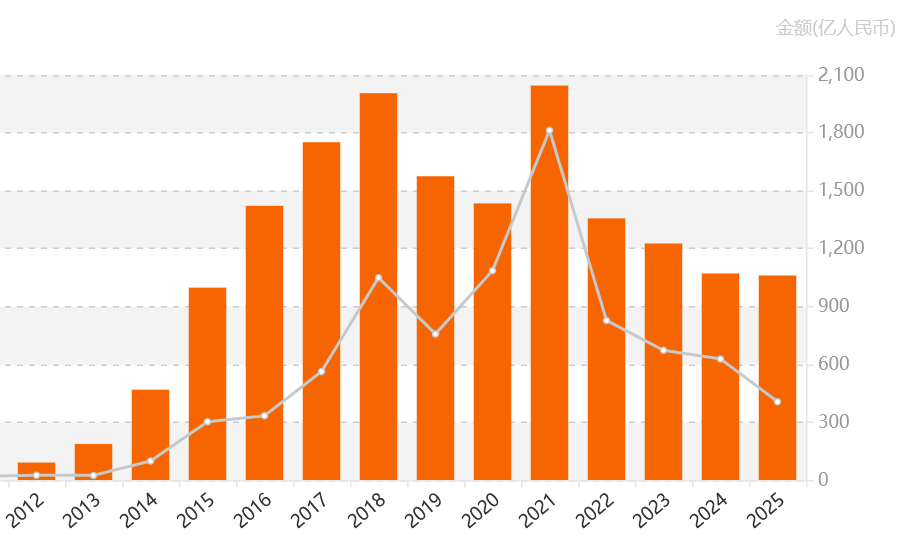

Chinese private investment in AI companies 2012-2025 (YTD)

The data comes from ITJuzi.com, one of the better providers of data on Chinese VC and tech funding (though none are perfect). The orange bars represent deal count while the grey line represents capital invested. This screenshot is missing it’s left axis (and the right is in Chinese) so I’ll pull some numbers.

Both deals and total capital invested peaked in 2021 at 974 investments worth approximately $25 billion USD. In 2024 those numbers were down dramatically to 510 investments worth $8.6 billion USD. In 2025 we’re on pace to substantially increase the deal count (already at 507 in early Sept) but to roughly equal the capital invested in 2024 (currently at $5.7 billion). Just looking at the direction of the lines, you’d think that we were in the midst of an AI winter. (And no, the DeepSeek moment from earlier this year didn’t set off an ever-mounting wave of VC investment — May through July saw a slight uptick but then back to previous levels in August.)

Contrast that downward arrow in China over the past three years with:

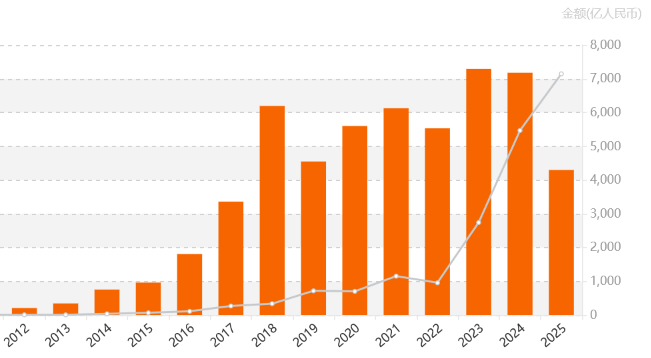

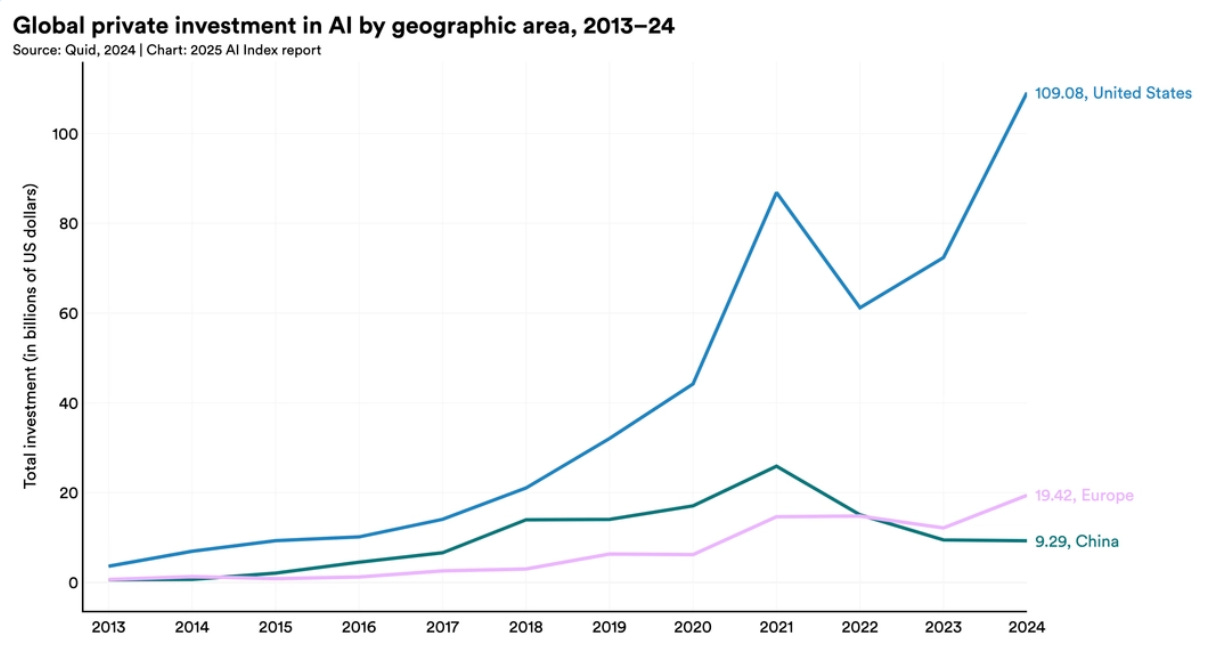

Global (non-China) investment in AI companies 2012-2025 (YTD)

Again, that grey line going steeply up is the total capital invested, reaching around $100 billion USD in 2025 YTD. Very different trend line. Data on investment totals can be all over the place, so for context here’s a comparable chart from the 2025 AI Index Report by Stanford HAI, pulling from different sources.

The bottom line is that in the nearly 3 years since the debut of ChatGPT, funding for AI companies in China has decreased. This is a reflection of the fact that the venture capital industry in China has been essentially decimated. For a good read on that decimation, check out this April 2024 piece from Robert Wu at Baiguan. It could be that the industry has now bottomed out and is ready to rise, but for various structural reasons (exit of USD funds, end of the first-ever 7-10 year cycle for lots of funds born in the 2010s, etc.) I don’t think it will be getting back to its 2012-2018 heyday anytime soon.

Aside from the specifics trendlines on funding, I think there’s a deeper issue at stake: lots of private investors and companies felt severely burned by erratic and largely unfriendly policymaking from 2018-2023, and they’re not in a hurry to rush back into whatever the government tells them is the next big thing.

Beginning in mid-2023 the Party has attempted to publicly re-embrace private companies (including the platform tech giants they spent the previous few years beating up), but that hasn’t turned investor or consumer sentiment around the way these governmental public displays of affection did in years past. It seems that trust has been broken in a way that’s not so easy to repair.

That hesitance undermines a key — maybe the key — mechanism driving the successful tech stimulus plans of the past. Yes, direct subsidies can be helpful, and government procurement + the opportunity to pilot certain technologies gives lots of startups some helpful runway to achieve liftoff. But those things also tend to come with a fair amount of paperwork and bureaucratic entanglement. Traditionally, the best startups in China try to avoid these government entanglements. Instead, it was the way major policies galvanized private capital and entrepreneurial energy that drove the technology forward.

Finally, beyond the financial and business sentiment issues, I think the complexity of integrating AI into most industries will pose a significant obstacle. During the Internet+ era, millions of restaurants and nail salons and drivers were pretty easily able to plug into a user-friendly internet platform (WeChat, Meituan, Didi, etc.) and both take orders and receive payments on there. That relatively lightweight, low-complexity connection was enough to generate a real economic boost for many small businesses, and to even upend whole industries. Some integrations were more extensive and complex, such as the way local governments used WeChat as a portal to accessing public services, a linkage that removed a whole lot of headaches for regular people used to long lines and lots of 没办法’s (“whattayagonnado”). But when compared with the complexity of integrating AI (whether LLMs or vision models) into industrial and corporate workflows, that all looks relatively simple.

In China, this move from mere “connection” (internet) to “empowerment” (AI) is being discussed as a reason why AI+ will be so transformative. Patrick Zhang describes this well in his fantastic Geopolitechs newsletter on AI+:

According to some experts, “Internet Plus” was about “connection” (连接)—linking information to redesign processes and improve efficiency. “AI Plus” builds on that by adding cognitive ability, moving from “information connection and diffusion” to “knowledge application and creation.” Its essence is “empower”(赋能). It promises to reorganize production factors, upgrade value creation models, transform organizational structures, and reshape governance.

I think they’re right about the potential economic upside over the medium- to long-term. But that reorganizing of production factors and transforming of organizational structures adds many, many degrees of difficulty to the process. Deeply integrating an LLM into the guts of a corporation, or intelligent robots into a factory’s production process, is a complex and friction-filled process. It will likely require either very sophisticated in-house technical talent, or lots of highly specialized startups that build unique products and do the leg-work of deep integration.

But both of those paths are rocky right now, and likely will be for the foreseeable future. Specialized startups need the kind of funding that just doesn’t appear to be there right now. And the companies that the CCP has the easiest time mobilizing are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), a group not famous for either their in-house technical talent or their nimbleness with new technology. Much was made of how SOEs and local governments rushed to adopt DeepSeek in the months after its release, but see the ChinAI newsletter from just a few months later for a reality check on that adoption (“shallow, narrow, and slow”).

Taking all of these things together, we have an extraordinarily ambitious tech stimulus plan — one that might even be very far-sighted in how it sees AI transforming economies and societies — but one that lacks the traditional levers or incentives that have made such plans so impactful over the past decade.

3. The Bullish Case for AI+: Policy as permission, data unleashed, and AI+Science

I’ll start the bullish case with some rebuttals of key points in the bearish case. Given how successful China has been at climbing the technological value chain (with smart policies providing key nudges along the way), you could argue that the burden of proof is more on the bears than the bulls here.

Local government funding shortages won’t undercut implementation:

The cash shortage isn’t equally distributed across Chinese local governments, and generally speaking the richer and more technologically advanced cities and provinces (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Shenzhen) are doing better. These are the places where AI+ will really launch from: Beijing, Shanghai and Hangzhou are the hubs for software-focused AI startups; Shenzhen is the global center of hardware innovation; and Guangdong provides a vast industrial playground for experimentation with AI integration. Local and national support for AI+ experimentation will work out the kinks and demonstrate the business case for this integration, at which point the private sector will naturally move in and take the campaign nationwide.

Private investment in AI is finally ready to rebound:

Yes, it’s been a rough ~3 years for private investment in AI, especially at the VC stage. But that was due to some extraordinary circumstances: the big tech crackdown (2020-2022/3), the huge Covid lockdowns of 2022, broad uncertainty about the economy coming out of Covid, and some very mixed signals from the Party-state when it came to AI. The government’s first reaction to the post-ChatGPT generative AI boom was extreme concern over the implications for online speech and information controls.

The CAC basically blocked the wide release of LLMs for the first 8 months of 2023, and then was still making companies wait months for a (de facto) license for these. It wasn’t until 2024 that the CAC began shifting from de-facto-licensing toward more streamlined registration of models, and it wasn’t until the DeepSeek moment of early this year that we really saw the government full-on embracing these companies. The AI+ plan is now the clearest and the highest-level signal that the state is fully embracing AI as a major economic force. It may take a minute for that to translate into concrete investments, but there is tons of pent-up capital that is ready to surge into these fields now that it knows where to go. Add to this the “quiet bull” in China’s stock markets and we are seeing many more realistic exit options for tech investors than ever before.

AI integration is hard, but no country is better positioned for this than China:

China’s vast industrial economy, paired with its unmatched hardware innovation ecosystem, will make it an absolute playground for the integration of robotics and intelligent automation into industrial processes. We’re already seeing the early stages of this with the boom in robotics startup valuations. Yes, this will be a process full of friction and failure, but that’s true everywhere and China has the benefit of close proximity between lab and factory floor. With the rise of China’s new generation of robotics startups, we will see an extremely tight cycle of iteration and experimentation. (Side note: I highly recommend subscribing to the Substack linked in the previous sentence, Hello China Tech by Poe Zhao. It’s like Stratechery for China tech and hugely informative.)

Ok, beyond those rebuttals there are also additional positive cases to be made for the AI+ plan. I’ll make three here: (1) Policy as permission, (2) data unleashed, and (3) AI+S&T.

“Policy as permission”

This policy document might not provide the concrete funding needed to deeply integrate AI into every industry listed. But it does give entrepreneurial Chinese officials a certain amount of political cover to go out and experiment with AI-related activities without fear (ok, with a little bit less fear) that they will be punished if those experiments don’t pan out. There remains the question of how you fund these experiments, but there are some low-cost policy interventions that could prove impactful.

Just a couple examples of low-cost interventions from the policy itself (I’m sure enterprising officials will think of far, far more):

“encourage universities to include open-source contributions in student credit recognition and teacher achievement recognition”

“Improve data property rights and copyright systems suitable for AI development, and promote lawful and compliant openness of copyrighted content formed by publicly financed projects.”

Counting open source contributions toward university credits is pretty novel and interesting, though admittedly quite marginal within the big picture. But…

Data unleashed

The data stuff might turn out to be far more impactful. Legal decisions are nominally “free,” and I think this document sends a signal to judges nationwide that their rulings on cases involving data, copyright, fair use, and AI should be “suitable for AI development.” Chinese courts have issued a mixed bag of rulings on these issues, with some major decisions on whether training data constitutes “fair use” still pending. This document could be an important political nudge toward rulings that give AI companies a freer hand with using copyrighted works as training data. When you compare that with Anthropic’s $1.5 billion settlement in a copyright case this week, that nudge could go a long way. Add in the forced opening-up of copyrighted content that was created by public funding (an overwhelming portion of academic work, and a lot of creative work as well) and that nudge goes even further.

And it’s not just loosening up on copyrighted data. China’s recently-created National Data Administration (NDA) has a mandate to turn data into a new “factor of production” (“生产要素”), alongside the traditional factors of land, labor, capital and technology. The NDA is under the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the country’s economic planner. Over the past two years the NDRC has been charged with guiding Chinese AI policymaking across the bureaucracy and corralling the different ministries. The NDRC was the actual author of the AI+ plan (which was then released by the State Council), and it quickly followed that with the “AI+Energy” policy, co-released with the National Energy Administration. In describing ways that AI can turbocharge the energy sector, that document made better sharing and utilization of energy data a core component, mentioning “data” 33 times.

If it turns out that a key component of AI diffusion involves the creation and open-sourcing of high-quality public datasets, the NDA could be a major accelerant in that process.

AI+Science and Technology

I saved this for last because (a) it might be the most important part, but (b) I don’t have a lot of useful stuff to say about it. Lots of the people who I most respect in this space think the most promising AI applications are in the “AI for science” realm. By placing this first among the six “key domains” for AI+, the Chinese leadership is likely indicating that they agree with that assessment. This week the People’s Daily published a piece by Zhou Bowen, director and chief scientist of Shanghai AI Lab, on the paradigm shift toward AI-driven scientific research (Claude machine translation here).

If this predictions of AI becoming a driving force in scientific breakthroughs pans out, and if the AI+ initiative significantly accelerates that nexus of work, then this could turn out to be a monumental decision. But to be totally frank, I don’t know whether the document will accelerate that nexus of work, because I don’t know what the main obstacles or bottlenecks to this kind of work are.

If the main bottlenecks are bureaucratic hurdles (lab or university policies that limit the use of AI in research), then this could have a major impact, unleashing a wave of wide-ranging experimentation with AI-empowered research by scientists across China. If it’s a matter of a marginal access to resources, the policy could also have a significant impact, pushing universities and institutions like the Chinese Academy of Sciences to reallocate some financial and computational resources towards this type of research.

But if the limiting factors on the AI+Science nexus are different from the above (e.g. hard technical capability limits) then it’s unclear how much impact the policy will have. I’m not the right person to answer that question, but I really welcome feedback from those who know this space well.

4. Conclusion: Where I land and what I’m watching

When I started writing this piece, I intended to just argue the bear-ish case. But in the process of doing that I found myself throwing in a bunch of caveats and “but maybe if” qualifiers. In the end, I decided better to lay out the bear and bull case in full. But I don’t want to fully duck the question with a “maybe this, maybe that” piece.

On balance, I lean toward the bear-ish case. Despite the theoretical 10-year time horizon for the AI+ initiative, I think these type of policy documents have the largest impact in the ~2 years after they’re released. And right now I think the fiscal conditions and business environment severely undercut the mechanisms by which these policy documents traditionally have impact.

If you’ll allow me one final hedge: There’s a decent chance that over the next 5-10 years China does end up successfully diffusing AI applications throughout its economy, maybe even faster than the U.S. does. But if they do succeed, it won’t be because this policy turbocharged adoption. It will be due to other factors: major recovery in the Chinese economy; technical innovations that ease integration frictions and make AI adoption far less costly; and perhaps important of all, the truly awe-inspiring tenacity of Chinese entrepreneurs who always find a way to squeeze any possible business opportunity for all that it’s worth.

In this way, I actually differ from Jeffrey Ding’s thesis on China’s “diffusion deficit” in technology: I think that over the past ~20 years China has done a pretty amazing job at continually using technological diffusion to lever itself up global value chains, from traditional manufacturing upgrades all the way through “Internet+” and even early waves of AI. But at this particular economic and political moment, I think the traditional policy playbook for turbocharging diffusion just won’t work as well as it used to. This relates to another idea that keeps nagging at me and that I hope to explore in a future post: when I look back at the 2010-2020 period, I increasingly think of China’s technological boom of that era as being as much (if not more) a product of the wider economic boom as it was a driver of it.

But I’ll save that for another time. Thanks for sticking with me (or skipping to the end). I plan to keep future posts shorter and sharper. And I welcome your feedback.

Best,

Matt

The way the document is written, it’s quite unclear whether these 70% and 90% penetration rates for intelligent devices refer just to the six key sectors, or to the economy as a whole. I’ve now asked a bunch of people, including some Chinese people with a legal / policy background, and have gotten a variety of different answers on that (with most also saying it just isn’t clear). In a way, it doesn’t really matter because (a) I think these are wildly optimistic, borderline impossible targets to hit, and (b) the fact that it was written so ambiguously, and that there is no way to measure it even if written clearly, indicates that these types of targets are more gestural than actual. See Jeffrey Ding’s latest newsletter on AI+ for more on this point.

Side note: I don’t know how to quantify this or even convey it, but part of the lived experience in China from 2008-2018 was this sense of massive amounts of capital just sloshing around society — not in the pockets of your normal friends, but everyone had an uncle or a classmate or their school’s dean or city’s mayor who was accumulating and throwing wild amounts of money.

Excellent work Matt!

I always enjoy your work on AI issues and I'm looking forward to reading this and other Substack posts!